The ferry ship eased out of Kagoshima New Port shortly after midnight on Aug. 6th, bound for Naha, Okinawa. We stood on the top deck and watched the lights of the city slide by. Our kayaks, loaded with two weeks of provisions and necessary equipment, were somewhere in the hold below. Another precious 2-week holiday had begun. We were heading south where the sea is brilliant blue and full of promise of adventure.

At 7pm the next day, exactly 24 hours after leaving Amakusa, we arrived at the expansive Naha New Port. In the fading daylight we hastily packed the boats and slid them down the narrow stairs of the tall concrete wharf into the tepid water. Awkwardly we launched; passing directly under the immense overhang of our ferry’s stern. We paddled along the long wharf, then an even longer breakwater; by the time we made it to the lighthouse at its end it was already quite dark. We stuck close to the tetrapods while a solitary vessel went by; we were invisible to them, which was just as well. Then finally, we paddled past the light into open water. A Jumbo Jet roared close overhead to land a short distance away at the Naha International Airport, built right on top of the shallow coral reefs that fringe every island here.

10km further west, under a full moon and a myriad lights illuminating brownish clouds over the city well behind us, we neared a group of reefs called Keise-jima, planning to camp on one of the sandbanks in the center. On attempting to penetrate the reef, however, we quickly became beached in shallow water still far away from dry sand. Realizing the inherent difficulties of doing this at night, and not feeling particularly sleepy anyway, we re-crossed into deep sea and headed another 12km west to Mae-shima, where an artificial channel through the reef was marked in the map. This we located without difficulty with the help of the GPS; it led to (surprise) an abandoned “deserted island beach and camping area” such as are (or had been) popular everywhere we’ve been so far in Japan. They were someone’s potentially clever idea to make a few bucks, but a general lack of tourist interest and the devastating forces of the typhoons usually get the better of these places. Here too, everything was in utter disrepair and we finally set the tent on the broken pier where we had landed.

The morning’s heat woke us up. We looked around at the scenery for the first time in full color. We were on the doorstep of the Kerama Islands, a tiny but well-known destination for Japanese sea-lovers. Through a geographic accident three or four of the small islands almost completely enclose an area of sea and reefs, which consequently remains relatively free of waves and yet clean and teeming with life. Thus the islands are popular with divers, whale-watchers, and the like.

During our preliminary research we even found processed satellite images revealing in great detail the location of coral for this area. Aiming for one such place now, we found we weren’t the only ones in the know: a bevy of rubber-clad divers was already plopping into the water from a number of moored motorboats. Full of curiosity, we pulled up our kayaks on the beach, donned our snorkel gear, and swam out for a look.

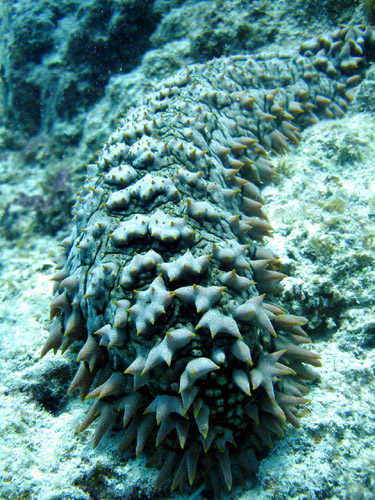

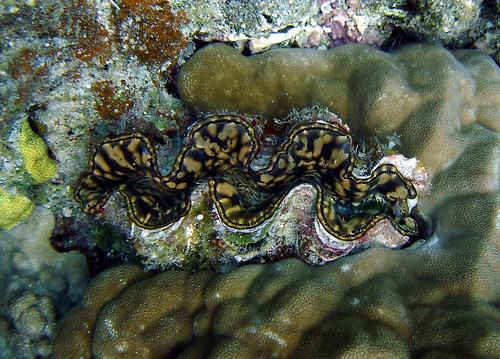

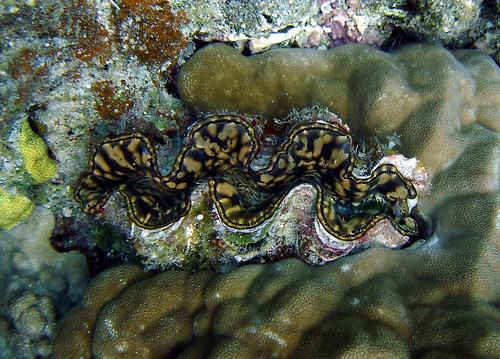

The water was pleasantly warm and a number of sea creatures could be seen on the seabed where rocks protruded from the sandy bottom. Large clams somehow perfectly fitted into pockets in the rock, and their delicate, colorful flesh revealed sinuous silky designs of many different colors.

Though we didn’t plan on it, curiosity somehow pulled us into the village of Zamami located on an island of the same name. A highly realistic whale “sculpture” reared out of the water at the port entrance. In the village we had geocoded a kayak shop so after an unexpectedly delicious and cheap lunch at the local cafeteria-style restaurant (with a great view of the seascape to boot), we wandered there. This was lucky in a way because at

Kerama Kayak Centre, the staff was friendly and gave us access to their Internet and sea charts, and we received a day’s warning of an incoming typhoon. All operations in the archipelago were to cease for the next 3 days. Knowing the Japanese to be overly cautious, we consulted our own sources and discovered that the next day would still be OK, but the typhoon would pass close on the day after next, making movement out of the question. The third day would again probably be OK.

This sent us scratching our heads. Slurping shaved ice on the street corner we formulated a plan: we would hang around tomorrow, then wait out the storm at a likely beach on nearby Aka Island, in the lee of the expected winds. We figured we would be protected from the onslaught of the storm by the mountain in the island’s center. Although a small town exists on the island, it would be on the windward side and we would have no recourse to civilization during the storm, as the map showed no roads or trails through the dense jungle backing the beach. Having never done this before, we felt somewhat apprehensive.

But after a short crossing, arriving at our beach, we found a dense clump of adan palm trees with a perfect space to camp underneath. The trunks and branches were short and flexible and would protect us from the storm without danger of breaking. The beach was high and in any case completely enclosed by a wide arc of reef where storm waves (though we did not expect any to come from this direction) would surely break up. Thus placated, we settled down and spent a quiet, peaceful evening and night.

At the Sakubaru viewpoint on Akashima.

At the Sakubaru viewpoint on Akashima.The weather the next day was glorious, as it nearly always is the day before a typhoon. The sky and the sea were a rich, deep blue. A stiff southeast breeze was the only obvious precursor to the storm. Since the weather was again behaving according to our expectations, we merrily ignored the Japanese warnings and set out on a most enjoyable circumnavigation of Aka and Geruma islands.

In the town of Geruma we visited a traditional house built about 150 years ago by a wealthy merchant. The elderly caretaker showed us pieces of WW2 shrapnel still embedded in the woodwork; apparently Kerama was the first place during the war to be attacked by American bombers.

Like most rural buildings in Okinawa, the house was surrounded by neat stone walls to protect it from typhoon winds, and, like all traditional Japanese dwellings, exuded the sense of balance with its surroundings that is so strikingly absent from nearly all modern structures here.

Like everywhere in Okinawa, a sanshin was at hand, and Leanne could not resist playing a tune or two, much to the delight of the old man who lamented that young people don’t learn traditional things anymore. How odd it must have seemed to him that a foreigner would paddle all the way here on a small boat, then pick up the local instrument and break into traditional Okinawa song. But he seemed to take it all in stride and told us which of the islands we were going to visit had the very poisonous, much feared but actually fairly rare snake called habu. He did not seem fazed at all by the hazard of the impending typhoon and approved of our plan to weather it, being familiar with the beach we chose and its orientation. He even told the neighboring innkeeper’s daughters that they are wasting their time boarding up the inn’s windows. “It’s not gonna be that bad”, he said. A bit embarrassed, they nevertheless continued their work.

We arrived back at our campsite just in time for a beautiful sunset. We listened to the typhoon reports on the AM radio, ignoring all information except the factual reports of its position, barometric pressure, and measured winds. Our campsite was just about line-of-sight with the cell phone antenna over Zamami village, and the phone occasionally sprang to life with more accurate forecasts pulled from the Internet and sent to us from Amakusa by our friend Kenji. Not much stood changed in the new forecasts; the typhoon would pass about 160km to the south of us at 6pm the next day. Final preparations were made, all things were put in waterproof bags and packed away; the boats were hauled into the thicket and tied to the trees with rope. We figured if things got bad we’d take down the tent and sit it out in the open under our clump of bushes.

It turned out we chose our location so well we never witnessed the storm in its full fury. Sure it was quite windy the next day, the sea was gray and heaving and gusts of wind were whipping salt water high in the air, but the full blasts of wind and the huge waves that must have battered the other side of the archipelago never reached us. Even at the height of the storm we could take a walk back and forth along our private beach, being blown by the wind only a little. We realized that being able to move before a storm and set up camp in a safe place is a very powerful strategy compared to, for example, weathering storms in our flimsy house back in Amakusa, where we had felt genuinely frightened on several past occasions. Here it was not even necessary to take down the tent and we spent the day in comfort lounging, listening to American National Public Radio (relayed through by one of Okinawa’s U.S. military bases), and napping. We would have to work hard during the next few days to catch up to schedule, so it was just as well we could use this day to gather strength.