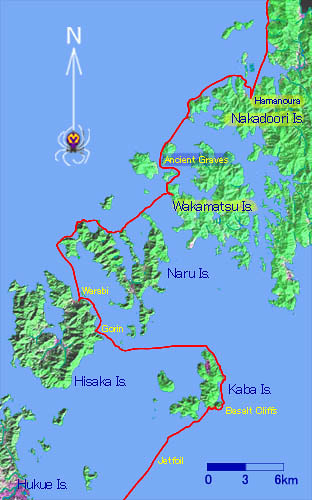

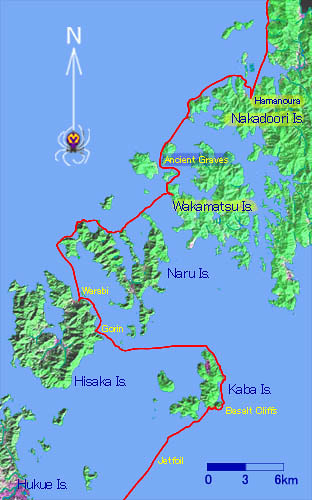

See the entire map of the

Goto Islands.

Red tide continues staining the sea as we begin a long, open crossing from the south-east corner of Hukue island over to Kaba island, where now a new danger is imminent. We are about to cross the path of the jetfoil boats that several times a day slice the water between Hukue and Nagasaki. We see a car ferry pull out of port and, timing its progress, we watch it descend slowly below the horizon. Its white smokestack disappears when it is only 10km away. The kayaker sits so close to the water that the Earth’s curvature severely limits her line of sight. Allowing also for the jetfoil’s slightly smaller size, at its cruising speed of 80km/h we will have only 5 minutes after we first spot it till it’s on top of us. At top paddling speed, we can cover about 700m during that time; thus a safe transit can be accomplished if one knows the ship’s route to this degree of accuracy. We had recorded our own ferry’s route, and now we are hoping the jetfoil will follow this path as well. Although its pilots must be looking for fishing boats in their way, kayaks are smaller and notoriously hard to see. Worse, they may be relying on their radar, which picks up the fishing boats but not kayaks. So we speculate about what to do if the brown stuff hits the fan: take off life jacket, tip the boat, then dive as deep and long as one can. If we time this right, it should be possible to dive to safety since the foils can’t be much deeper than 2 meters below the surface. Also we should separate so if one kayak gets shredded we can both limp to shore on the other. It seems scary to ponder so we get pretty nervous. 1 km from ground zero we begin our sprint across, intently scanning the relevant bits of horizon: Leanne back and left toward Hukue, I on the 2 o’clock position toward Nagasaki. And, as luck would have it, at exactly 80m short of intercept I see a white spot on the horizon, precisely in the expected direction. Too late to turn back now, so we sprint for it; a minute or two later the speck has not gotten any bigger and turns out to be only a fishing boat. But 10 minutes later, we see the jetfoil, and at about the same time can also hear the roar of its engine. Safe now, we watch him pass at a 1.3km distance, 6 minutes after first sighting it. We think how the safety margin might have been increased: fly a radar reflector, use the topography better and cross nearer land where the ship’s track may be more certain, and check the ferry schedule…though there’s no guarantee the boats will follow that, especially during the hectic tourist season.

Soon after we reach the cliffy south shores of Kaba-shima, the scenery awes us with its beauty: steep columnar basalt cliffs drop directly into the sea. The detour has been well worth it. We enter some interesting caves, wary of the deafening crashing of the sea swell deeper within. This outlying, sparsely habitated island turns out to have some of the most spectacular natural scenery in Gotou, although due to its position is not visited very often. We figure the fishing on these rocky shores would be excellent, but we do not see a single fisherman. Maybe it is too expensive to take a boat taxi this far out.

Night falls upon us as we re-cross open water back west toward the main archipelago, but the sea is calm and the only boats around have already settled into position for a night of squid fishing, having turned on their powerful lights that blind us even from a distance. Where our prows and paddles cut the water thick with red-tide plankton, it gives off a psychedelic phosphorescent glow, so bright sometimes that it lights up our faces from below in a ghostly way. As we approach Hisaka-jima we look for a place to land and camp, but in the dark this is rather difficult, as nice-looking beaches turn out to be nothing but rough boulders and gravel.

Eventually we find a narrow space on top of a derelict, stinky, abandoned concrete structure. Judging by the distribution of oyster shells the tide covers most of this, so we crowd the tent onto a section we hope won’t get flooded. While doing this, the already rising water dislodges my boat, which drifts away; a classic gumby mistake. Leanne paddles around in circles in the pitch darkness while I ride the back of her kayak scanning the water with my headlamp for the runaway boat. Fortunately we find it quickly. We lift the boats onto some rocks and exhausted, hit the sack. During the night we don’t get flooded and the morning dawns bright and clear.

A short paddle takes us to Gorin church, certainly one of the most valuable cultural artifacts of the archipelago. Made of wood by a local carpenter more than 100 years ago, it is preserved today only through the concerted efforts of conservationists (the village, consisting of one house and no road, already has a new church).

From the outside, the church evidently looks much the way an ordinary house used to look around that time, while the inside has vaulted (“bat-wing”, as the Japanese like to say) ceilings and the unmistakable feel of a Christian church.

Its beauty resides in its simple design. We are moved by this cultural treasure more deeply than by any other during this journey.

We navigate the Naru Strait and then turn north-east along the north shores of Naru and Wakamatsu islands. The north shores of Naru are wild and precipitous, but Wakamatsu with its low hills, complex shoreline, and many outlying islets is more habitable.

Twisting through some narrow straits between these, we find an old graveyard, evidently from the Kamakura Period, though new stones have been added as if for decoration. Though the surroundings have been built over in the standard pointless fashion (toilets, artificial beach, concrete blocking the strait that once served as an entrance into the calm inland anchorage), the place still induces a kind of spiritual feeling. Though the hour is late and camping here would be ideal, we must move on; we paddle away into the dusk and strengthening wind.