Nippo Coast Kayak Trip

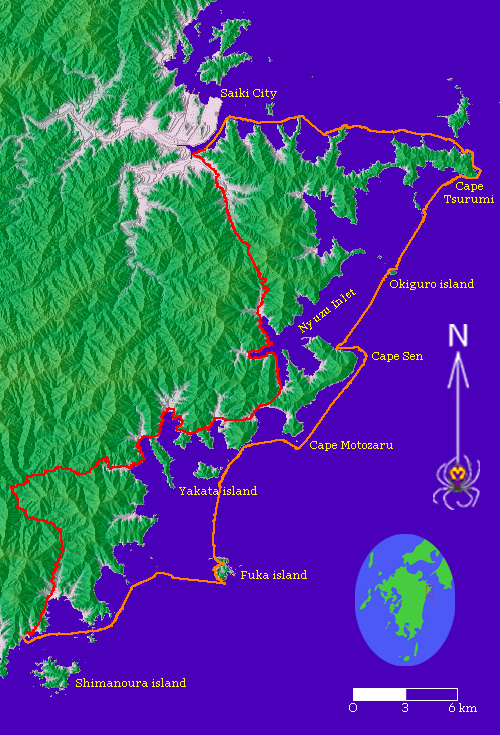

The Nippo Kaigan is a rias coast forming the easternmost part of Kyushu. Across the Bungo Strait to the east, Shikoku, the smallest and least developed of Japan’s four main islands, casts a distant mountainous silhouette. The Nippo coast is rugged and riddled with peninsulas and bays. To the north lies Japan’s Inland Sea, and to the south, the open Pacific; consequently, strong tidal currents flow, and the sea is rarely resting even in calm weather. So was the case this mid-July weekend, when we chose to traverse a 70km stretch of the Nippo coast, between the village of Aso in Miyazaki Prefecture and the industrial city of Saiki in adjacent Oita Prefecture.

A typhoon was raging about 1500 kilometers away in southern Okinawa, and although here the weather was settled and calm, long waves from the typhoon had had no trouble traversing the intervening distance, arriving at 10 second intervals and a height of about 2 meters. Relative to the familiar waters of the East China Sea, the restless surface of the ocean evoked a distinctly different gut feeling.