31N/130E - Kuroshima

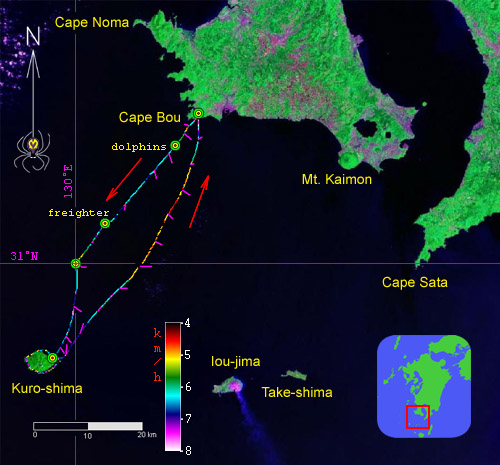

A LANDSAT image forms the background of this map of our excursion to Kuroshima. The color-coding of our tracks show variations in speed relative to land, mostly due to the sea-currents, which are also shown in magenta along our tracks at a scale of 1km to 1km/h. It took 10 hours to get to Kuroshima (including about 40 minutes circling about the confluence), and 11 hours to get back (non-stop).

It’s an hour or two after our midnight departure and the night is dark and as yet moonless, though the splendid summer stars provide a minimum of light to get by. The Milky Way arches overhead, and a shooting star occasionally falls towards the horizon. The starry sky is an excellent compass, and we keep the constellation Scorpio directly ahead of us to maintain our south-south-westerly course. The sea is flat now and there is little wind so far, but we had just crossed through patches of breaking waves made by the mixing currents here off the southwest corner of Kyushu. Presently, from the starboard quarter the sound of more waves slowly comes closer. But wait, something’s odd; it’s not quite a wave sound. “Stop paddling for a second”, I say to Leanne, “Let’s listen.” It’s actually a sea-mammalian breathing sound, coming closer and closer. Then I see a dorsal fin right next to my boat – “Dolphins!” We resume paddling as a small pod of dolphins swims along just off to starboard. The curious creatures must have wondered what those strange splashing sounds were that we were making with our paddles. Now they playfully dive under our boats, invisible in the night but painting beautifully curving ribbons of phosphorescence with their tails. At first, this kind of closeness to one of the sea’s powerful creatures is a little disconcerting, but they obviously mean no harm. Ten minutes later, they are quietly gone. It’s only then that I realize that the snorting sounds (which they stopped making once alongside), and their careful, slow approach from the four o’clock position, were as if to say, ‘Don’t be startled, we come in peace.’ Contrast this with the so many ‘helpful’ fishermen, who approach us perhaps thinking we are in trouble, engine on full power and their frothing bows aimed directly at us – a sight that my nerves have yet to get used to. Dolphins truly are intelligent creatures, and this chance meeting again reminded us of why it is exactly that we choose to spend our free time monotonously paddling the seas.

We’re on the way to Kuro-shima (Black Island), an isolated, mountainous island about 5km across, 54 km SSW from our departure point near Cape Bou, Kyushu’s southwest extremity. The island is part of the Osumi Islands, a loose archipelago of three well separated islands and some rocks and reefs, of which

Kuroshima is the biggest. Perhaps more interesting is Iou-jima (Sulphur Island) 30km E of Kuro-shima, with its active volcano, but today we have an ulterior motive: on the way to Kuroshima is the ‘confluence point’ 31N 130E of latitude and longitude lines, as yet unvisited as per the Confluence Project website. After ‘bagging’ this, our plan calls for a landing on Kuroshima to regain our strength, perhaps circumnavigating the island to enjoy its coastal cliffs and waterfalls, then paddle back the next day. We chose this weekend, with less than ideal weather for paddling, because the visibility was expected to be good (for photos from the confluence). Knowing that we might have to fight a strong wind on the way back, we feel the commitment increasing with every paddle stroke to the south.

Kuroshima is the biggest. Perhaps more interesting is Iou-jima (Sulphur Island) 30km E of Kuro-shima, with its active volcano, but today we have an ulterior motive: on the way to Kuroshima is the ‘confluence point’ 31N 130E of latitude and longitude lines, as yet unvisited as per the Confluence Project website. After ‘bagging’ this, our plan calls for a landing on Kuroshima to regain our strength, perhaps circumnavigating the island to enjoy its coastal cliffs and waterfalls, then paddle back the next day. We chose this weekend, with less than ideal weather for paddling, because the visibility was expected to be good (for photos from the confluence). Knowing that we might have to fight a strong wind on the way back, we feel the commitment increasing with every paddle stroke to the south.

A crescent moon rises and a north wind picks up, gradually gaining in strength as expected. We have to avoid quite a few freight ships, most fully loaded with containers. It’s hardly surprising that it’s so busy here, since most shipping heading for Osaka or Tokyo from points in Korea and China would logically pass through here. As this is still basically open sea, the ships’ courses are very straight and easy to avoid, though once we are fooled by the sheer enormity of a freighter, decide erroneously not to cut in front, then have to wait as the behemoth grows bigger and bigger in the uncertain dawn light, finally passing seemingly too close in front of us. As we resume our own course, we see that it is actually a better part of a kilometer before we intersect the ship’s wake: we were fooled again by the ship’s enormous size, even at relatively close quarters.

Sunrise finds us less than 10km from the confluence; the wind blowing hard now and kicking up big waves. Leanne’s super light Solander kayak (borrowed from our friend Kenji) surfs on them like a piece of styrofoam, and I am nearly having trouble keeping up in one of our old plastic clunkers. Arriving at the confluence, I take the necessary pictures for entering into their website. Visibility is quite good: Kuroshima is prominent to the south, 18km distant, a silhouette of Iou-jima can be seen 36km to the southeast, and the coast of Kyushu we had left more than 6 hours ago can also be made out, 34km to the north. It’s quite challenging to take a picture of the GPS reading the exact zeroes of the confluence, what with the 2-meter waves, wind and current drift, and bright sunshine reflecting off the plastic bag that protects the unit from seawater. After a number of passes I manage it however, and we move on.

Kuroshima is about 7km distant here.

After the confluence we can finally alter our course fully downwind and we truly get flying on the waves. With the seas washing over our decks, we approach the condition of ideal kayaking excitement. Water drips in through our spray skirts though, and bailing is necessary every hour or so. The sea feels warm, due to the influence of the Kuro-shio (Black current, the equivalent of the Atlantic Gulf Stream), and the water is of a clean blue color that is never seen in Amakusa, though it doesn’t approach the electric blue so typical of Okinawa.

As we fast approach Kuroshima we see the north coast properly roughed up by the waves, making the planned beach landing inconvenient if not dangerous. We head instead toward hulking concrete breakwaters of the port of Osato. On entering the port, we spot a sea turtle: always a sign of good luck. Minutes later, our luck meets us in the form of a welcome delegation. A dozen of the village’s 100 or so inhabitants appear on the pier, shouting excitedly. Of course they are surprised to learn where we came from, especially so because we unwittingly corroborate a Kuroshima story from WW2, when locals rescued a downed kamikaze pilot and delivered him back to the mainland, via a 32-hour voyage on a primitive sculling boat. The pilot tragically met his death a while later, assigned to yet another kamikaze mission, but as he flew over Kuroshima, he helped save some lives by dropping off some desperately needed medicine. The story seems fully believable to us, but to the young locals it had started to seem a bit incredible perhaps – after all you can’t see land to the north in all but the clearest weather. Now seeing living proof that it can be done, their belief seemed restored. Having done the traverse in 10 hours ourselves, we may conclude a kayak is about 3 times faster than a sculling boat, which actually seems about right.

Leanne steps up the excitement level among the kids one more notch by dusting off her diving skills and pulling off a neat somersault off the pier. Having originally planned to avoid the towns for fear of frightening the locals, our visit now takes on an unexpected human element. The folks who met us turn out to be mostly teachers and students at the local school, which they are eager to show us as soon as we get out of our wetsuits. The facility functions as a combined elementary and junior high school, and with less than 20 students and about 8 teachers, the kids here can be assured of a top quality education, especially with the infectious attitude of the teachers. In Japan, job transfers are mandatory especially in the public sector, and many young public servants end up hating their exiles to the remotest corners of their prefecture, yearning for the city jobs that are waiting for them after they pay their dues. Thus we often run into disgruntled people on our rambles through the boondocks. But every one of these young teachers had actually requested to be transferred to the sticks, and they are loving it. Furthermore, all but one of the junior high school students are actually from places like Tokyo or Osaka, having opted to come here under a program that encourages city kids to experience country life.

Our kayaks rest on the slope in this view of the port from near the school.

Together these folks have created a mini-utopia here. If the government pulled the funding for places like this, Kuroshima would become uninhabited in a short time, having no hope of being economically self-sufficient. It’s good to see tax money being spent on actually making people happy.

A simulated aerial view of Kuroshima, using LANDSAT data. North is to the right and the scale varies; in any case the island is about 5km in diameter. Kayak paths (approach, return, circumnavigation) are shown in orange, while the numerous roads contouring the mountainsides are shown in red.

After a tour of the school, we retire to the house of one of the teachers for a coffee break. The wide sweep of sea visible from his living room is peppered with whitecaps today. After chatting for a while, Leanne is offered a futon for a badly needed nap while I amble back down to port with plans to circle the island by kayak. Minutes out of port, at the east end of the island where a strong north-setting current is shedding away from the shore in a series of eddies, I am somewhat surprised to see several sizeable sharks circling around, presumably looking for an easy lunch of fish disoriented by the swirling water. As one swims directly under my boat, I catch the distinctive profile of a hammerhead. Too slow on the draw with the camera, I miss the opportunity for a good picture. Initially a bit curious, once the sharks realize I am after them, they scuttle away.

Kuroshima is very mountainous and except for where the two towns lay, tall steep cliffs ring the island. Streams descending from the mountains tumble over the cliffs in tall waterfalls, some splashing directly into the sea. Not a sign of human intervention here (one is hardly possible in such a landscape), and even the usual garbage that litters the beaches is scant. What with the sharks and all, this place has the feel of a true wilderness.

Three hours later I am back just as two of the teachers return from a successful fishing outing and plans are afoot for a barbecue. At this rate, I’ll get no sleep for the second night in a row! I grab about an hour’s nap before the fish and steaks are grilled up. Time goes by fast as we chat and munch away. At 10 o’clock, we sneak off to the school to check the weather forecast on the Internet, and are pleased to find it has changed for the better. To take the advantage of a calm spell we set departure time at 1:30am and grab a few hours of deep sleep.

Before we know it we’re on the water again, the lights of the village receding into the distance, and the beam of the lighthouse sweeping across the dark horizon. The sea is totally calm - a complete change from just hours ago. Freight ships again ply the passage but this time none comes close enough to necessitate any change in course on our part. The moon rises again, then the sun, directly behind the conical Mt. Kaimon, Japan’s most perfect imitation of its famous Mt. Fuji. Next begin a tough several hours, as sleepiness overtakes me on the calm sea. As I struggle to stay awake, I eventually notice it is possible to paddle and sleep at the same time. Through hours of unwitting conditioning, my brain has learned to turn off all but the rowing and balancing systems. Occasionally I wake up with a start when my paddle unexpectedly hits a small wave, realizing that I’ve been paddling, asleep with eyes closed, for some time. Leanne, it turns out, is doing the same thing. Sleeping like this certainly makes the time go by faster, but it’s actually kind of tiring, plus one’s power output necessarily drops. But I wonder what is possible with further training.

Before we know it we’re on the water again, the lights of the village receding into the distance, and the beam of the lighthouse sweeping across the dark horizon. The sea is totally calm - a complete change from just hours ago. Freight ships again ply the passage but this time none comes close enough to necessitate any change in course on our part. The moon rises again, then the sun, directly behind the conical Mt. Kaimon, Japan’s most perfect imitation of its famous Mt. Fuji. Next begin a tough several hours, as sleepiness overtakes me on the calm sea. As I struggle to stay awake, I eventually notice it is possible to paddle and sleep at the same time. Through hours of unwitting conditioning, my brain has learned to turn off all but the rowing and balancing systems. Occasionally I wake up with a start when my paddle unexpectedly hits a small wave, realizing that I’ve been paddling, asleep with eyes closed, for some time. Leanne, it turns out, is doing the same thing. Sleeping like this certainly makes the time go by faster, but it’s actually kind of tiring, plus one’s power output necessarily drops. But I wonder what is possible with further training.

The Kyushu coast is still about 20km distant, during the return paddle.

Finally at about 9:30 I emerge from the world of half-sleep and hallucinations, into a bright and increasingly hot morning. Realizing I’m already overheated, I splash water on myself and drink plenty of sports drink. Too late: a headache and lethargy will be my companions for the rest of the day. Leanne has also picked up questionable company: a shark has been swimming casually on her tail for several hours. Perhaps these creatures are used to trailing fishing boats, devouring innards and junk fish thrown overboard, but why do they always follow her instead of me? When I approach to get a closer look, the shark scuttles. Quite a different disposition from yesterday morning’s dolphins, these sneaky sharks have. Anyway he does not seem intent on outright hostilities and is in any case too small to cause serious harm, so we just paddle on, ignoring him.

12 o’clock, 11 hours after setting out, we pull up on the concrete slope where we left exactly 36 hours ago. It’s a hot, sunny, calm day; a few fishermen are on the pier and a family is enjoying a snorkeling outing. The slim young mother, sans wetsuit, impresses us by swimming nimbly out and diving in deep water. As we slip into the sea, it feels a bit cold still for such activity, but this also is due to our exhaustion and overheating. (We will spend the rest of the day somewhat feverish, devouring ice creams to cool down. Really, heat exhaustion is the main thing to be concerned about during summer paddles.)

Lethargically, we put away our equipment in and onto the car, then drive up to the hill where a clutch of wind turbines slowly turns in the light breeze; these giant structures have formed a landmark to aim at ever since it got light enough to see. The road is closed just short of the summit and we have no energy to walk up. But even from here, the view of the sea is impressive: due to the Kuro-shio current impacting onto Kyushu, the first major landmass obstructing its flow, the water is covered with giant streaks and creases like the snout of a bulldog. (Crossing these on the way in, we had felt the direction and speed of the current change each time.) Barely discernible beyond a great blue expanse of water, Iou-jima and Kuro-shima hover like ghosts on the horizon. The life we had experienced there, if ever so briefly, seems a life fundamentally different and significantly more enjoyable than that of the mainlanders. Already it is just a memory, as untouchable as the shadow of distant Kuro-shima.

黒島の新しい友達へ

黒島はほんとうに宝島ですね!色々案内してくれて本当に面白かったです。いい思い出がいっぱいできました。また黒島に行きたいです!英語の勉強を頑張ってください。また会いましょう!

1 Comments:

You did it Congratulations! Sounds like a sort of fun and definately impressive.

By Anonymous, at 11:42 am

Anonymous, at 11:42 am

Post a Comment

<< Home